Why You Keep Making the Same Bad Decisions Under Pressure

Jan 23, 2026

You’re evaluating a complex acquisition. Three teams have presented conflicting analyses. The board wants your recommendation by end of week. Normally, this is the kind of problem you navigate well: weighing trade-offs, integrating multiple perspectives, tracking implications across timeframes.

But this time, something feels different.

You find yourself circling the same argument without resolution. Alternatives that should be obvious keep slipping away. New data arrives, but it does not integrate cleanly with what you already know. Your thinking feels narrower, more repetitive, less adaptive, even though nothing about your intelligence or experience has changed.

This is not a personal failure. It is a predictable shift in how working memory behaves under pressure.

This article examines what happens to working memory when cognitive systems operate under stress, why this produces oversimplification and rigidity, and what evidence suggests can support decision quality once those limits are reached.

Working Memory Is the Workspace That Holds the Decision Together

Working memory is what allows you to hold information in mind, update it as conditions change, and compare alternatives in real time. It is the workspace where you evaluate trade-offs, detect inconsistencies, plan sequences, and adjust course mid-execution.

It is also fundamentally limited.

Even under ideal conditions, working memory has finite capacity. You can only hold so many variables, constraints, and options simultaneously before the system saturates. Under stress, that already limited capacity shrinks further.

The evidence is consistent across behavioural and neuroimaging studies. Stress is associated with slower reaction times, reduced accuracy, and diminished ability to maintain task-relevant information during cognitively demanding tasks (Andrzejczak & Liu, 2010; Nwikwe, 2025; Verhallen et al., 2021). At the neural level, stress reduces functional engagement of prefrontal regions that support working memory and cognitive control (Haucke, Golde, & Heinzel, 2025).

From a systems perspective, this is not a defect. It reflects a trade-off: when threats are detected, cognitive architecture prioritises speed and salience over integration and flexibility.

The problem for senior decision-makers is obvious. The decisions that matter most require exactly what stress degrades: the ability to hold multiple considerations in mind and integrate them without collapsing the model.

For a deeper explanation of this mechanism, see the pillar article: Working Memory Under Load.

Why Stress Shrinks the Mental Workspace

Under pressure, cognitive resources do not simply operate at reduced efficiency. They are reallocated. Several mechanisms drive this.

Internal noise competes for capacity

Stress introduces intrusive thoughts, worry, and anticipatory monitoring. These are not passive distractions. They are active processes that consume working memory resources.

As internal noise increases, less capacity remains available for holding the variables, constraints, and alternatives your decision requires (Nwikwe, 2025).

In practice, this looks like reduced mental bandwidth taken up by background processes you cannot fully switch off.

Neural resources shift toward salience

Under stress, neural activity shifts toward emotionally salient and threat-sensitive regions, including the amygdala. This reallocation draws resources away from prefrontal systems responsible for working memory maintenance and flexible control (Becker, Volk, & Ward, 2015).

The outcome is fast orientation to threat-relevant cues and a reduced capacity for integration and deliberation. The system is tuning for survival conditions, not strategic planning.

Representations become less stable

Stress reduces the stability of working memory representations, especially when distraction and task switching are present (Haucke et al., 2025). Information becomes harder to hold over time.

You might notice this as losing track mid-argument, or finding that points you understood clearly five minutes ago now feel vague and harder to retrieve.

How Reduced Capacity Produces Oversimplification and Rigidity

When working memory capacity shrinks, the system compensates by simplifying.

Oversimplification: treating a multi-variable problem as a single-variable problem

Attention narrows to a smaller subset of available information. Problems get treated as if they have fewer dimensions than they actually do. Secondary constraints, longer-term implications, weak signals, uncertainty ranges, and soft operational risks are often the first to drop.

Not because you are careless, but because the workspace cannot hold the full model.

Stress-related working memory reductions are associated with reduced information sampling and increased error rates in complex decision environments (Andrzejczak & Liu, 2010).

When this happens, decisions tend to be made on the basis of the loudest variable, not the most predictive one.

Perseveration: repeating the same reasoning because switching is too expensive

Working memory supports cognitive flexibility by allowing you to hold multiple representations simultaneously and switch between them. When capacity is constrained, switching becomes costly.

Under stress, people are more likely to:

-

repeat previously reinforced strategies even when they are no longer effective

-

reuse familiar arguments without updating them

-

rely on older, automated knowledge rather than integrating newly learned information

-

get stuck revisiting the same set of considerations without forward movement

This reflects a shift from flexible, goal-directed control toward more rigid stimulus–response patterns (Luksys & Sandi, 2011; Shields, Sazma, & Yonelinas, 2016).

In executive settings, this can look like a decision loop that feels busy but produces no new synthesis.

The critical distinction: capacity support vs flexibility under load

Some interventions can support working memory capacity at the margins. None reliably restore cognitive flexibility once you are under high load.

Popular discussions blur this distinction. The evidence does not support the idea that supplements, dietary optimisation, or productivity routines can prevent oversimplification or rigidity once working memory is saturated.

What they may do is influence how quickly limits are reached, or modestly raise the threshold at which degradation begins. That is useful, but it is not the same as maintaining flexible, adaptive thinking under sustained pressure.

What evidence suggests can support working memory capacity

This section is not a protocol. It is an orientation to the evidence and its likely interpretation.

Physical activity

Among behavioural interventions, regular physical activity, particularly resistance training, shows consistent associations with preserved working memory performance, especially in older adults (Bai et al., 2026). Proposed mechanisms include neurotrophic support, improved metabolic efficiency, and increased tolerance for cognitive load.

This does not guarantee better judgement. It appears to increase the point at which load begins to compromise working memory.

Nutritional patterns

Evidence favours multi-nutrient dietary patterns over isolated supplementation. Combined intake of omega-3 fatty acids, carotenoids, and vitamin E has been associated with modest working memory improvements over long timeframes, with stronger effects as cognitive load increases (Power et al., 2022; Meroni et al., 2025).

Acute macronutrient effects (glucose or protein ingestion) can transiently influence working memory performance, but effects are time-dependent and task-specific (Jones, Sünram-Lea, & Wesnes, 2012).

Overall, effects are small, slow to manifest, and strongly context-dependent.

Creatine

Creatine is one of the few supplements with reasonably consistent evidence for reducing mental fatigue and producing modest working memory improvements under specific conditions, including high cognitive demand and sleep deprivation (Allen, 2012).

Mechanistically, it likely supports cellular energy availability rather than cognitive strategy. In practical terms, this suggests capacity support, not improved flexibility or insight.

If you are already using creatine, this is the correct expectation: it may help with tolerance and fatigue margins. It will not prevent rigidity once saturation occurs.

When strategy matters more than capacity

Once working memory limits are reached, additional capacity support offers diminishing returns. At that point, strategy changes matter more than physiology.

The most reliable way to preserve decision quality under reduced capacity is not to expand the mental workspace. It is to externalise information, reducing what must be held in working memory in the first place.

This is why high-reliability domains use checklists, structured briefings, and external decision aids. Not because experts lack competence, but because competence does not override biological capacity limits.

Recognising cognitive rigidity: observable markers

Cognitive rigidity is not subjective discomfort. It has observable markers. You are likely seeing it when you notice:

-

Repetitive loops: returning to the same line of reasoning without integrating new information

-

Alternative collapse: struggling to hold competing options in mind at the same time

-

Single-constraint fixation: over-relying on one metric while losing sight of other constraints

-

Dismissal blindness: being unable to articulate why certain alternatives were rejected

-

Model thinning: the decision model loses variables over time, not because they were resolved, but because they fell out of working memory

A micro-case makes this visible.

You are in the board meeting. Someone asks, “What is the integration risk, realistically?” You know there are at least five interacting variables: systems compatibility, leadership continuity, customer churn, regulatory timing, operational capacity. You have already discussed all of them.

But in the moment, your model collapses to one metric. EBITDA. Or headcount synergy. Or timeline.

You repeat the same argument, slightly rephrased. You feel the missing variables, but you cannot hold them in mind long enough to reconstruct the full picture. The room moves on. The decision narrows. Not because the other variables disappeared, but because your cognitive workspace could no longer carry them simultaneously.

When this pattern appears, working memory is operating at saturation. More effort usually increases friction. Structural intervention is the appropriate response.

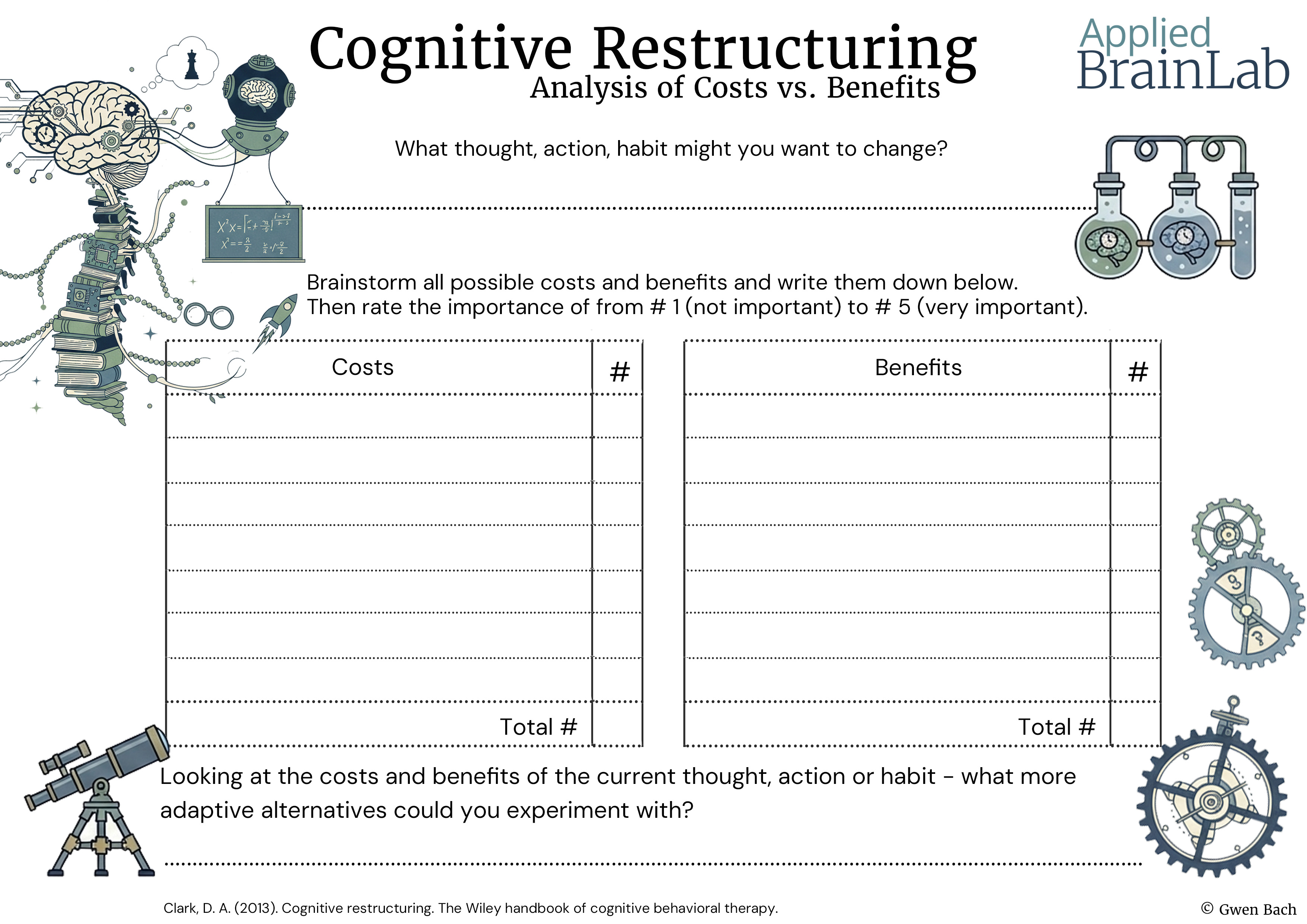

Cognitive Restructure Worksheet: a tool for the rigidity marker

This is the simplest way to think about the worksheet:

Problem: working memory saturation is producing rigidity.

Solution: move the decision model out of working memory and into external structure.

Like a hammer, the value is not its origin story. The value is that it reliably does one job.

The Cognitive Restructure Worksheet is designed for a specific failure mode: perseveration and oversimplification caused by a reduced working memory workspace. When the rigidity marker is present, it helps you externalise the model so the system can work with it again.

What the worksheet helps you do

-

Externalise variables that keep dropping out of consideration

-

Lay constraints side-by-side rather than serially cycling through them

-

Expose assumptions that are currently running as default settings

-

Rebuild alternatives that collapsed when capacity narrowed

-

Create forward movement by converting a loop into a structured comparison

When to use it (examples)

Use the worksheet when you recognise the rigidity marker in situations such as:

-

you keep repeating the same argument and cannot generate a new synthesis

-

the decision keeps narrowing to one variable despite evidence it is multi-variable

-

you are unable to state clearly why an alternative was dismissed

-

you have multiple stakeholders and cannot hold their constraints simultaneously

-

new data arrives but does not integrate cleanly with the current model

In these conditions, the worksheet does not make you think better. It reduces the load required to think at all.

Download the Cognitive Restructure Worksheet (free).

Connection to the broader framework

This article connects directly to the broader examination of decision degradation under stress explored in the pillar post.

Stress does not create new cognitive limitations. It exposes existing ones by reducing available capacity and changing how resources are allocated. Oversimplification and rigidity are not signs of poor judgement. They are predictable outputs of a biological system operating beyond its optimal range.

Closing perspective

Working memory degradation under pressure reflects trade-offs built into human cognition. These trade-offs favour speed and salience over completeness and flexibility.

Understanding these limits allows you to interpret cognitive shifts accurately. Not as personal failures, but as signals of load.

When capacity is constrained, the goal is not optimisation. It is reliability. Reliability often means knowing when to move information out of your head and into external structure, not because you cannot handle the decision, but because the system you are working with has predictable limits.

References

Allen, P. J. (2012). Creatine metabolism and psychiatric disorders: Does creatine supplementation have therapeutic value? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(5), 1442–1462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.005

Andrzejczak, C., & Liu, D. (2010). The effect of testing location on usability testing performance, participant stress levels, and subjective testing experience. Journal of Systems and Software, 83(7), 1258–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2010.01.052

Bai, Y., Yuan, Y., Qiu, B., et al. (2026). Effects of different non-pharmacological interventions on executive function in healthy older people: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 143, 106141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2026.106141

Becker, W., Volk, S., & Ward, M. (2015). Leveraging neuroscience for smarter approaches to workplace intelligence. Human Resource Management Review, 25(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2014.09.008

Haucke, M., Golde, S., & Heinzel, S. (2025). Development and validation of the socio-evaluative N-back task to investigate the impact of acute social stress on working memory. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22611-0

Jones, E. K., Sünram-Lea, S. I., & Wesnes, K. A. (2012). Acute ingestion of different macronutrients differentially enhances aspects of memory and attention in healthy young adults. Biological Psychology, 89(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.12.017

Luksys, G., & Sandi, C. (2011). Neural mechanisms and computations underlying stress effects on learning and memory. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 21(3), 502–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2011.03.003

Meroni, M., Longo, M., Paolini, E., & Dongiovanni, P. (2025). A narrative review about cognitive impairment in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Journal of Advanced Research, 68, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.02.007

Nwikwe, D. (2025). Effects of stress on cognitive performance. Progress in Brain Research, 291, 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2025.01.015

Power, R., Nolan, J. M., Prado-Cabrero, A., et al. (2022). Omega-3 fatty acid, carotenoid and vitamin E supplementation improves working memory in older adults. Clinical Nutrition, 41(4), 877–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.12.004

Shields, G. S., Sazma, M. A., & Yonelinas, A. P. (2016). The effects of acute stress on core executive functions. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 68, 651–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.038

Verhallen, A. M., Renken, R. J., Marsman, J. B., & ter Horst, G. J. (2021). Working memory alterations after a romantic relationship breakup. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 15, 657264. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2021.657264

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.